Lumbosacral stenosis is a spinal condition of dogs (and less commonly cats) that resembles a ‘slipped disc’ or ‘sciatica’ in people. Back pain is the most common sign of this condition in pets, although some patients with nerve compression may also appear to be lame. An MRI scan is necessary to diagnose the condition. As in people, many patients with lumbosacral stenosis can be managed successfully with conservative treatment, although surgery is occasionally necessary to relieve the pressure on trapped nerves.

What is lumbosacral stenosis?

Lumbosacral stenosis is a neurological condition where nerves at the base of the spine are compressed by a bulging disc or other tissues. The lumbosacral disc is the last disc in the lower back between the seventh lumbar vertebra and the sacrum. Ageing may result in dehydration and degeneration of this disc which may then bulge (protrude) and compress or ‘trap’ regional nerves. The resultant narrowing of the canal in the spine (the vertebral canal) or the exit holes between the bones (the vertebral foramen) is referred to as stenosis. The underlying cause of the disc degeneration and bulging is unclear, although in some dogs it is associated with instability of the bones of the spine.

Large breeds of dogs are more commonly affected with lumbosacral stenosis than smaller breeds, and German Shepherd Dogs and Border Collies appear to be particularly prone to the condition. It is an uncommon complaint in cats.

What are the signs of lumbosacral stenosis?

Back pain is the key clinical feature of the disease. Typically, affected animals are reluctant to jump and climb, and they may have difficulty rising from a lying position. Groaning or spontaneous yelping may be a feature. Less common signs include hind limb lameness (due to spinal nerve compression), incontinence and reduced tail movement.

A German Shepherd Dog with lumbosacral stenosis that is reluctant to go up a small flight of steps due to back pain. Note also the dropped tail associated with the spinal nerve compression

How is lumbosacral stenosis diagnosed?

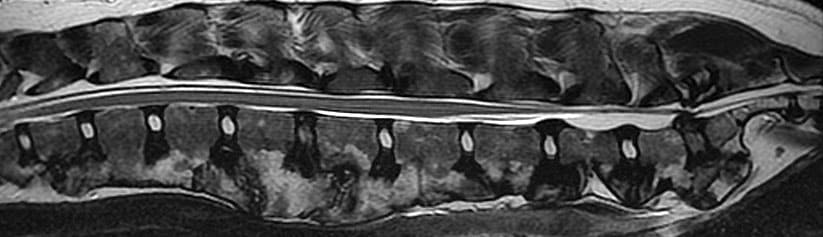

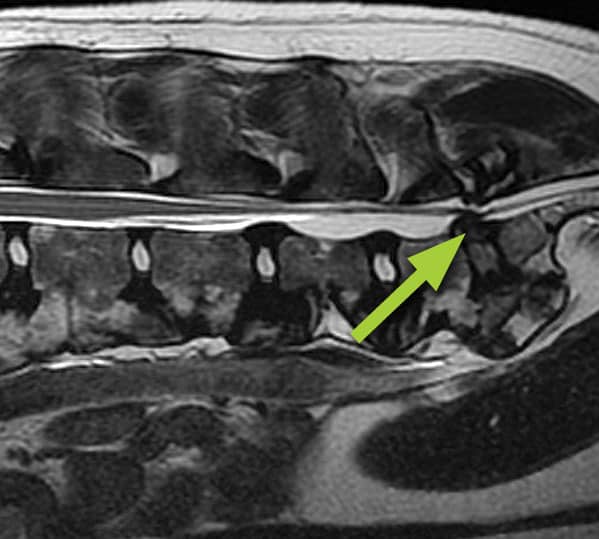

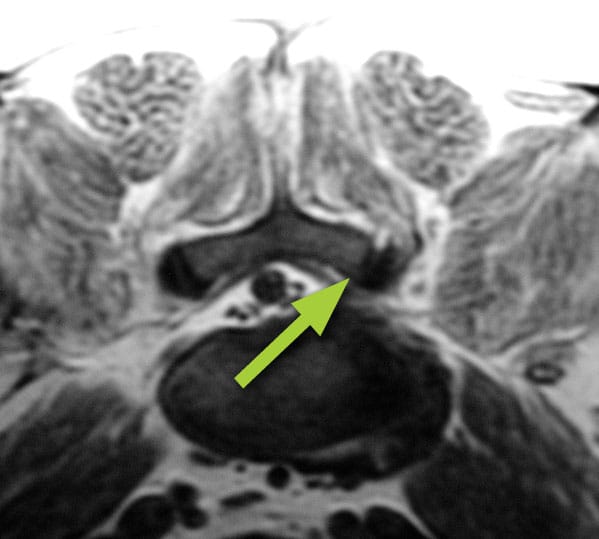

Radiographs (X-rays) of the spine are primarily useful to rule out other causes of back pain, such as infection or tumour. They show bony tissues and are therefore poor for investigating lumbosacral stenosis, since the condition primarily involves the lumbosacral disc and regional nerves which are soft tissues that don’t show up on X-rays. Other X-ray imaging techniques, such as myelography and CT scanning, are also of limited value. MRI scanning is the best method (the ‘gold standard’) for investigating many spinal conditions, including lumbosacral stenosis. MRI scanning uses high powered magnets and a computer to generate images of the spine (this is the same technique and the same equipment which is used for body scanning in human patients). It provides detailed information on the location and extent of any soft tissue compressions of the spinal nerves in the lumbosacral spine.

MRI scan along the length of the spine showing lumbosacral stenosis due to a protruding (bulging) disc (arrow)

MRI scan across the spine showing lumbosacral stenosis due to a protruding (bulging) disc that is compressing the nerves on this side of the spine (arrow)

How can lumbosacral stenosis be treated?

As in people with back pain associated with a ‘slipped disc’ in the lower back, the majority of dogs and cats with lumbosacral stenosis can be successfully managed without the need for surgery. It is often necessary to modify exercise with avoidance of strenuous activities that involve jumping, climbing, twisting and turning. Dogs should initially be walked on a lead (short distances frequently) and exercise should be gradually increased over a number of weeks. Overweight patients should be placed on a calorie restricted diet. The majority of affected animals will benefit from receiving pain killing medications. Anti-inflammatory agents, neuropathic drugs and muscle relaxants may all be beneficial. Lumbosacral stenosis may also be managed by injecting a long-acting steroid (cortisone) around the compressed spinal nerves via a lumbar puncture. Repeat injections may be necessary in some patients. The technique necessitates a general anaesthetic.

Some patients with lumbosacral stenosis require surgery in order to relieve pain, hind limb lameness and other clinical signs. Various techniques may be performed, and these aim to remove pressure on compressed nerves and/or stabilise the lumbosacral spine. Removing bone from the top of the spine is referred to as a laminectomy, whilst enlarging the exit holes between the bones (the vertebral foramen) is referred to as a foramenotomy. Bulging disc material and other soft tissues that are compressing spinal nerves are removed. The lumbosacral bones (vertebrae) may be stabilised by the insertion of screws or pins that are secured with metal bars or cement.

X-ray following lumbosacral stenosis surgery showing multiple pins embedded in cement that were used to stabilise the spine

What is the outlook (prognosis) in patients with lumbosacral stenosis?

The majority of dogs and cats with lumbosacral stenosis can be successfully managed with exercise regulation, weight control and medical therapy. Once signs have improved or have been resolved, it is often possible to gradually increase exercise and reduce or stop medications. ‘Lifestyle’ changes may be necessary – for example, it may be necessary for the activity of an agility dog to be modified. As in people, flare-ups are not uncommon and these may necessitate further periods of medication and restricted exercise. In those patients requiring surgical management, most respond favourably following appropriate postoperative rehabilitation, although recurrence of back pain can be a feature in some cases.

We are always happy to discuss any aspects of a case with you or your vet prior to referral. If you have any questions or concerns please contact us.

Arranging a referral for your pet

If you would like to refer your pet to see one of our Specialists please visit our Arranging a Referral page.