Mast cells are normal cells found in most organs and tissues of the body, and are present in highest numbers in locations that interface with the outside world, such as the skin, the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract (stomach and bowels). They contain granules of a chemical called histamine which is important in the normal response of inflammation.

When mast cells undergo malignant transformation (become cancerous), mast cell tumours (MCTs) are formed. Mast cell tumours range from being relatively benign and readily cured by surgery, through to showing aggressive and much more serious spread through the body. Ongoing improvements in the understanding of this common disease will hopefully result in better outcomes in dogs with MCTs.

Why do dogs get Mast Cell Tumours (MCTs)?

This is unknown, but as with most cancers is probably due to a number of factors. Some breeds of dog are predisposed to the condition, and this probably suggests an underlying genetic component. Some dogs also have a genetic mutation in a protein (a so-called receptor tyrosine kinase protein) which inappropriately drives the progression of mast cell cancer cells.

The role of these receptor tyrosine kinases in canine MCTs is very interesting and also important in understanding the role and mechanisms of the newer drugs available for treating canine MCTs: the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (see Treatment Options).

Where in the body do MCTs occur?

The vast majority of canine MCTs occur in the skin (cutaneous) or just underneath the skin (subcutaneous). In addition, they are occasionally reported in other sites, including the conjunctiva (which lines the eyeball and eyelids), the salivary glands, the lining of the mouth and throat, the gastrointestinal tract, the urethra (the tube from the bladder), the eye socket and the spine.

A mast cell tumour on the muzzle of a Labrador Retriever

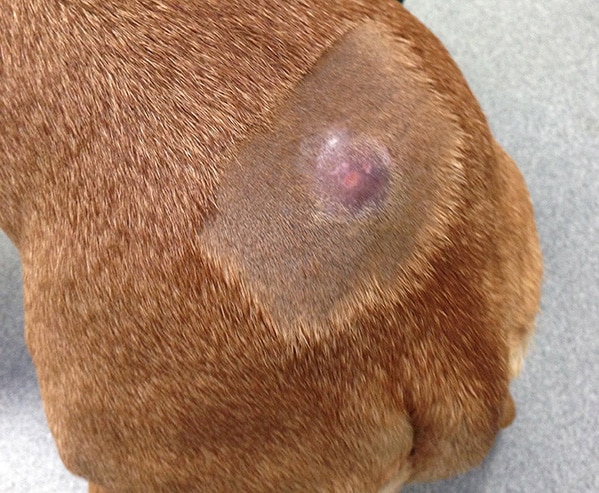

A mast cell tumour on a dog’s back

Breed predisposition

Some breeds of dog are predisposed to getting mast cell tumours (see table).

| Some of the breeds predisposed to mast cell tumours | |

| Australian Cattle Dog | Fox Terrier |

| Beagle | Golden Retriever |

| Boxer | Labrador Retriever |

| Boston Terrier | Pug |

| English Bull Terrier | Rhodesian Ridgeback |

| Bullmastiff | Schnauzer |

| Cocker Spaniel | Shar-Pei |

| Dachshund | Staffordshire Terrier |

| English Bulldog | Weimaraner |

Some breeds tend to get MCTs more commonly in certain locations, but more importantly MCTs sometimes behave in a certain way in certain breeds. For example, Pugs are renowned for getting large numbers of low-grade (less aggressive) tumours, and Golden Retrievers commonly get multiple tumours. Boxers with MCTs are generally younger than other breeds, and more commonly have lower-grade MCTs with a more favourable prognosis. In contrast, Shar-Pei’s usually get aggressive high-grade and metastatic (spread to other sites) tumours, often at quite a young age.

Age

The average age of dogs at presentation is between 7.5 and 9 years, although MCTs can occur at any age.

Paraneoplastic syndromes and complications of granule release

Cancerous mast cells may contain more histamine than normal mast cells. Histamine is a very inflammatory chemical, and therefore explains why some MCTs wax and wane or suddenly increase in size due to inflammation – especially after they have undergone biopsy/needle aspiration (see diagnosis). Histamine also causes the stomach lining to produce more acid – this can result in stomach ulcers, which, in extremis, can cause signs such as vomiting or black, tarry stools (this appearance is due to the presence of digested blood coming from the ulcer).

The outlook (prognosis) –

Can we predict whether a dog will do well or not do well due to their MCT?

No single factor accurately predicts the biological behaviour or response to treatment in dogs affected by MCTs. Various clinical factors are associated with a poorer outcome, such as the breed of the dog, as already mentioned, whether the tumour has spread and also the tumour location.

Tumours in the nail bed, underneath the tail and in the groin area are often correlated with a worse prognosis than those in other parts of the body. Tumours which arise internally, though unusual, are typically more advanced before they are recognised and so these patients tend to do less well than those presenting with a simple cutaneous mass.

If there is a single most valuable factor in predicting the outcome for most patients, it is the grade of the tumour when assessed under a microscope (the histological grade). For this, a biopsy is required.

How is MCT diagnosed?

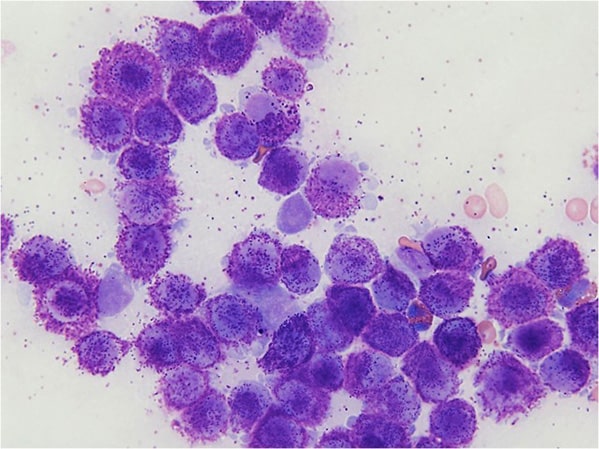

Cytology

Cytology means looking at the cells under a microscope, and the sample for this is usually obtained by ‘fine-needle aspirate’. Fine-needle aspirates of MCTs involve taking a small sample of the tumour with a thin needle. This is generally a straightforward procedure which can be done conscious and without sedation in most patients. It should be performed prior to any surgery, because a pre-operative diagnosis of MCT influences the type and extent of surgical intervention required.

Mast cells from an aspirate, seen under the microscope – they contain and shed typical granules. They are stained purple in this sample.

Biopsy

This involves taking a larger piece of tumour tissue and sending it away to a pathologist for analysis. This can be very instructive in the decision about the best treatment for the patient.

The pathologist looks at the sample of the tumour under the microscope and designates a tumour grade according to strict criteria. This grade is used to indicate how aggressive the tumour is likely to be.

MCT grade and outlook (prognosis)

Low grade (grade 1) tumours and around 75% of intermediate (grade 2) tumours are cured with complete surgical excision. Unfortunately, most high grade (grade 3) tumours and around 25% of intermediate grade tumours have already spread by the time they are diagnosed (even if this spread cannot be detected on scans at the time of diagnosis). These cases are likely to benefit from additional medical treatment. In some dogs, further analysis of the biopsy samples is useful in determining the best management options.

The tumour grade is very important in determining the appropriate therapy for dogs with MCTs.

Further investigations – ‘staging’ of the MCT

As well as performing fine needle aspiration and biopsies of the MCT to determine its grade, additional tests may be required to determine the stage of the tumour i.e. whether or not it has already spread. These further tests can include sampling of nearby lymph nodes, chest X-rays and abdominal ultrasound scanning. Which tests are performed will depend on a number of factors, and these will be discussed with you by the Specialist.

Treatment options

Surgery is the cornerstone of management of MCTs, and complete surgical removal is often curative in dogs with low or intermediate grade MCTs. However, to achieve a cure, in some circumstances a significant amount of tissue surrounding the tumour must be excised to ensure that all the tumour cells are removed. This can require a high level of surgical experience and expertise, in order to perform complex reconstructive surgical techniques – we are able to provide this expertise at North Downs Specialist Referrals.

If complete removal is not possible, or where the tumour appears to be more aggressive (e.g. high-grade) then radiation therapy, chemotherapy and other anti-cancer drug therapy treatments become more useful. The optimum treatment depends on the tumour grade, stage and other factors unique to the individual dog.

Anti-cancer drug therapy can be used –

- before surgery to shrink a tumour down

- after surgery if the Specialist considers there to be a risk of metastasis (spread) or incomplete removal

- as the mainstay of treatment in cases where surgery is considered to be inappropriate due to a high risk of spread, tumour development in an inoperable location or even, if an owner or the Specialist simply does not want to pursue surgical intervention, for example, due to the age of the patient.

Fortunately, the drugs used for chemotherapy in MCTs are extremely well-tolerated and most owners are very happy with their dog’s quality of life on treatment. An integral part of any chemotherapy programme is an ongoing and open conversation about the patient’s well-being on therapy. Although problems are uncommon, if there are problems, it is critical that all owners understand that the treatment plan can be changed to reduce or remove the risk of treatment-related side effects. The guiding principle of therapy is to improve quality of life, not to make it worse!

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors – ‘Designer Drugs’

A new group of drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors is also available, we call them ‘designer drugs’, (This isn’t a term we expect you to find on Google, we made it up, but it does characterise these medicines well.) Tyrosine kinase inhibitors, rather than being modified versions of natural products as most medicines are, are actually designed by computer software for a very specific purpose. They really are very clever, they block proteins (called tyrosine kinases) which are found on the surface of cancerous mast cells, and which are instrumental in the growth of many of the more aggressive mast cell tumours. These can be used where tumours are particularly aggressive, cannot be surgically removed or have recurred despite previous treatments. They can have some side effects, but the side effect profile is different from what one would expect with conventional chemotherapy; most dogs tolerate these drugs well.

Clinical Trials

The oncology Specialists at NDSR have years of experience of being at the very forefront of care with canine mast cell tumours. Our pedigree has led to us being asked to trial a new chemotherapy treatment and to advise in Europe and the USA on the use of this product. Similarly, our oncology team led in the clinical application of one of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapies now licensed for use in dogs with mast cell tumours and indeed, were invited to then share knowledge with the European veterinary oncology community through lectures and scientific presentations. This remains an active area of research, so do please ask about this if/when you meet with one of the oncology Specialists.

Best Treatment Selection

NDSR has internationally recognised Specialists in the fields of both medical and surgical oncology, and is a leading centre for cancer treatment in dogs and cats. The expertise provided by the combination of medical and surgical cancer Specialists has particular advantages in MCT treatment, and enables us to ensure that the best treatment is chosen in each individual patient.

Summary

Mast cell tumours are surprisingly common in dogs. They usually arise in the skin (almost always). They are famously variable in their behaviour. The ability to correctly predict the behaviour of the tumour enables the practitioner or Specialist to offer the best advice concerning treatment. Behaviour is defined by many factors but the most consistent of these is the tumour grade.

It is important to remember that most dogs with mast cell tumours will be cured by surgery. However, some dogs will not be cured. So long as the tumour behaviour is correctly predicted, appropriate medical therapy can be offered. Many cases, even with more aggressive tumours, can be managed in such a way that an excellent quality of life can still be enjoyed for a prolonged period of time.

If you have any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Arranging a referral for your pet

If you would like to refer your pet to see one of our Specialists please visit our Arranging a Referral page.